When a group of seven or so highschoolers walk together, they will spread out long, like a cordon sweeping across the sidewalk. Nobody wants to be the one who is behind the group. So they walk side-by-side, shoulder-to-shoulder. They will subtlely push people off the path so that they can pass by in their own carnival parade. They don’t have to be feeling particularly obnoxious to do this.

Yesterday, one of those teenagers was not just obnoxious, but aggressive. She was very pretty — stunning, in fact. Anybody would have noticed her, especially because her features were unique. Clearly, she had albinism, there was no pigment in her skin or hair. She was paper-white and lovely. She was accustomed to the stares, I’m sure. However, she chose to deal with that fact strangely. I walked behind her group of friends, so I happened to witness how many times she stuck her hand out in front of a stranger’s face and waved wildly.

“Hi!” she blurted in a loud and silly way. She and all her friends would laugh when the passer-by looked up (none had been staring before she accosted them) and appeared startled at the sight of her. It was as if she wanted to pre-empt public curiosity with her own poor manners. I longed to commiserate with her AND to correct her at the same time.

“Yeah, sometimes the stares are annoying, dear, but that stranger COULD have been staring because you are beautiful, you know,” I would have said. “Some people are just absent-minded when they are staring, not malicious; they would be so embarrassed if you drew it to their attention. Why be tacky? Smile back. That’s all. Be gracious.”

Then I would have given this young woman an example from my life this week. A little girl (about five) was riding a Razor scooter beside her jogging daddy and they zipped toward me on the sidewalk. She stopped abruptly and stared, mouth gaping, at my legs.

“Why does she go like that, walking?” she said out loud. (I thought the syntax of the sentence was cute). Her father, who had stopped as well, put his arm around her shoulder and kept leading in the direction they were headed. I winked at him as he passed. He smiled. It was okay.

“Because that is the way she walks, sweetheart. Do you remember when we talked about the way that everyone is different …” He valued her curiosity enough to give her a legitimate answer. Great dad.

Kids get a free pass, just so you know. I mean, I have been in supermarkets when a kid asks a question like this out loud, and the father or mother is so humiliated that he or she immediately apologizes to me (why?) and reprimands the child sharply, “Don’t ask that out loud! Leave her alone! I’ll tell you about it in the car.”

I think an inquisitive child deserves an answer, and in the past I have walked back to the shopping cart with a big smile and told the little one that it was quite all right to ask me questions. Then I explained a bit about my disability to him. It takes two sentences. The poor parent is relieved. The child smiles appreciatively. It is not his fault that he ended up with a mom who doesn’t show respect to her own kid. When the mother or father doesn’t show respect for the intellect of the child, then I know they didn’t really have that much respect for me either. It’s all a facade.

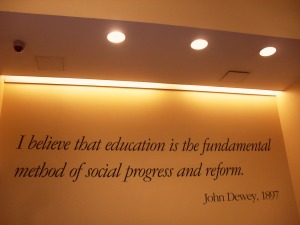

I do think there needs to be a lot of social progress and reform, and it begins with some basic education. Here’s how I wish it would happen: start with the kids, who are innocent. There are three steps.

In front of and with your kids …

1. Try not to say anything derogatory about parking that is reserved for persons who are disabled (things like: “Why are there so many parking spots, when they are never all used at the same time?” or “Maybe I can just park here for a second and leave it running with y’all inside. I only have to get one thing.” or “I sure wish I could park close, too” — I hear that one at least twice a month). By the way, NEVER borrow your grandmother’s handicapped parking placard and then expect your child to grow up with integrity.

2. Have a decent and respectful conversation — about disabilities, about cultural differences, about ethniticies, about religious practices, whatever– BEFORE the embarrassing grocery store incident occurs. You can always start the disability strand with … “You know, everybody on this planet is different. That is what’s cool about being alive; no one is the same. People even get around in different ways, and some of us use helpful tools like wheelchairs or canes …” (When I began this conversation with my 3 yr. old niece, she said, “You mean the way I have to use the scooter to get around at the grocery store?” I said, “Well, not exactly …” Obviously, she sits in my lap on the grocery store mart cart pretty often).

3. Enjoy all kinds of friends who are different in all kinds of ways. Let your little ones get used to the idea that not everyone looks the same or does things the same way. All types of people are walking side-by-side and shoulder-to-shoulder in life. Nobody likes to be the one behind the group.

That said, you will probably be embarrassed in the grocery store anyway. But don’t kick yourself or scold your child. Kids need encouragement in order to keep the light of curiosity blazing in their minds. The last thing we want to do is to turn it off. I’m a teacher. Trust me on this one.